Update [2020-05-14]: Bezos Conveniently Ignores Congress's Call to the Hot Seat

Amazon.com Inc. employees have used data about independent sellers on the company's platform to develop competing products, a practice at odds with the company's stated policies.

The online retailing giant has long asserted, including to Congress, that when it makes and sells its own products, it doesn't use information it collects from the site's individual third-party sellers -- data those sellers view as proprietary. Yet interviews with more than 20 former employees of Amazon's private-label business and documents reviewed by The Wall Street Journal reveal that employees did just that. Such information can help Amazon decide how to price an item, which features to copy or whether to enter a product segment based on its earning potential, according to people familiar with the practice, including a current employee and some former employees who participated in it.

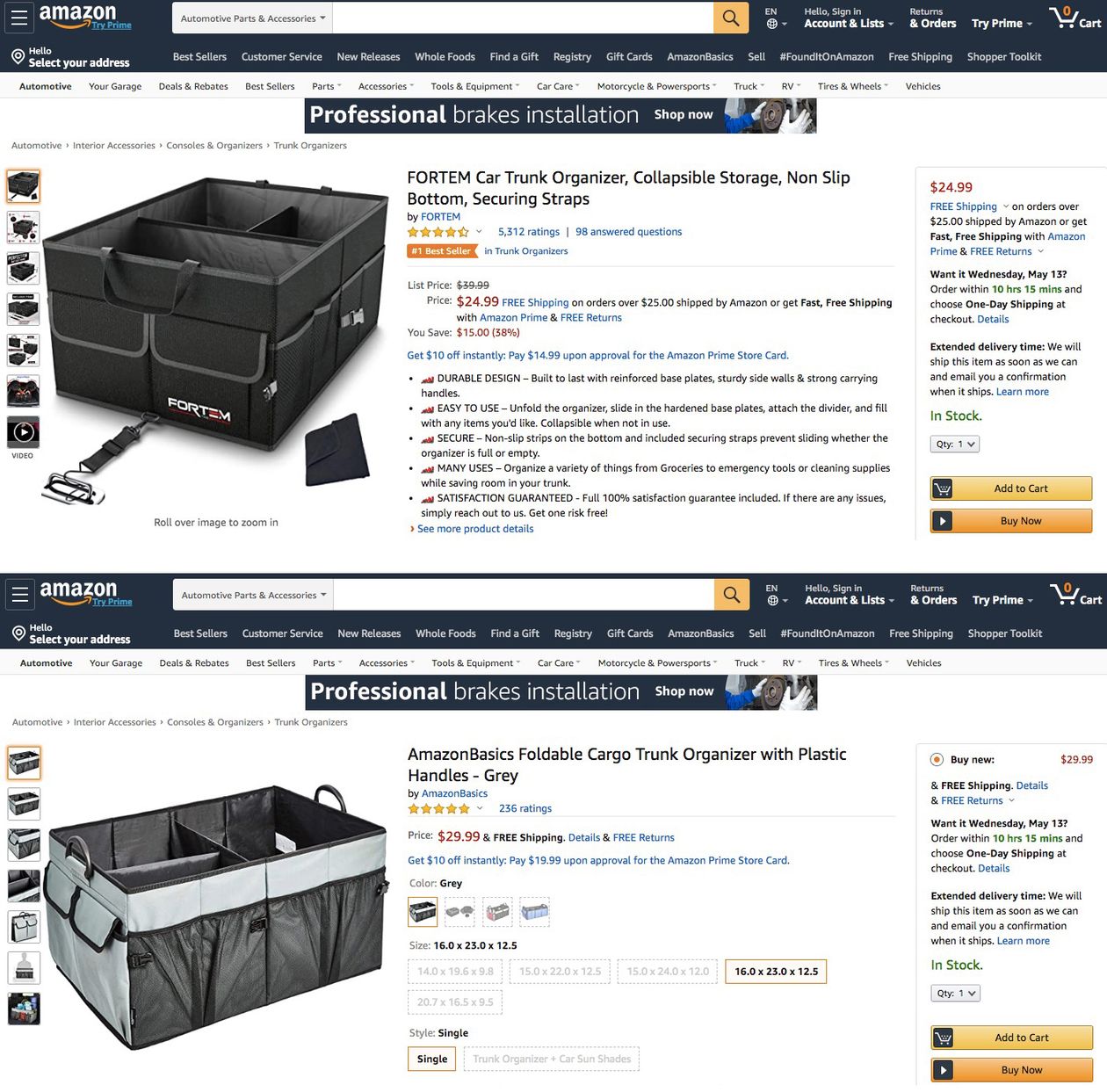

In one instance, Amazon employees accessed documents and data about a bestselling car-trunk organizer sold by a third-party vendor. The information included total sales, how much the vendor paid Amazon for marketing and shipping, and how much Amazon made on each sale. Amazon's private-label arm later introduced its own car-trunk organizers. "Like other retailers, we look at sales and store data to provide our customers with the best possible experience," Amazon said in a written statement. "However, we strictly prohibit our employees from using nonpublic, seller-specific data to determine which private label products to launch."

Amazon said employees using such data to inform private-label decisions in the way the Journal described would violate its policies, and that the company has launched an internal investigation. Nate Sutton, an Amazon associate general counsel, told Congress in July: "We don't use individual seller data directly to compete" with businesses on the company's platform.

It is a common business strategy for grocery chains, drugstores and other retailers to make and sell their own products to compete with brand names. Such private-label items typically offer retailers higher profit margins than either well-known brands or wholesale items. While all retailers with their own brands use data to some extent to inform their product decisions, they have far less at their disposal than Amazon, according to executives of private-label businesses, given Amazon's enormous third-party marketplace.

The coronavirus pandemic has enabled Amazon to position itself as a national resource capable of delivering needed goods to Americans sheltering in place, garnering it goodwill in Washington. The company continues, however, to face regulatory inquiries into its practice that predate the crisis.

Last year, the European Union's top antitrust enforcer said that it was investigating whether Amazon is abusing its dual role as a seller of its own products and a marketplace operator and whether the company is gaining a competitive advantage from data it gathers on third-party sellers.

The Justice Department, Federal Trade Commission and Congress also are investigating large technology companies, including Amazon, on antitrust matters. Amazon is facing scrutiny over whether it unfairly uses its size and platform against competitors and other sellers on its site.

-

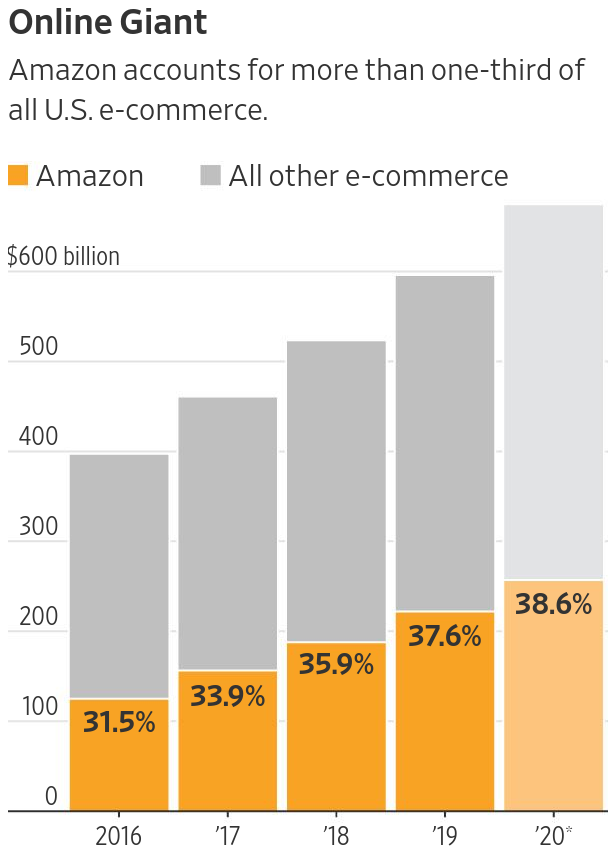

[Amazon retail sales. Image source. Click image to open in new window.]

Amazon disputes that it abuses its power and size, noting that it accounts for a small proportion of overall U.S. retail sales, and that the use of private-label brands is common in retail. Amazon has said it has restrictions in place to keep its private-label executives from accessing data on specific sellers in its Marketplace, where millions of businesses from around the globe offer their goods. In interviews, former employees and a current one said those rules weren't uniformly enforced. Employees found ways around them, according to some former employees, who said using such data was a common practice that was discussed openly in meetings they attended. "We knew we shouldn't," said one former employee who accessed the data and described a pattern of using it to launch and benefit Amazon products. "But at the same time, we are making Amazon branded products, and we want them to sell."

Some executives had access to data containing proprietary information that they used to research bestselling items they might want to compete against, including on individual sellers on Amazon's website. If access was restricted, managers sometimes would ask an Amazon business analyst to create reports featuring the information, according to former workers, including one who called the practice "going over the fence." In other cases, supposedly aggregated data was derived exclusively or almost entirely from one seller, former employees said.

Amazon draws a distinction between the data of an individual third-party seller and what it calls aggregated data, which it defines as the data of products with two or more sellers. Because of the size of Amazon's marketplace, most products have many sellers. Viewing the data of a product with a number of sellers wouldn't give it insight into proprietary seller information because the figures would show lots of different seller behavior.

Amazon said that if there is only one seller of an item, and Amazon is selling returned or damaged versions of that item through its Amazon Warehouse Deals clearance account, Amazon considers that "aggregate" data -- and hence is permissible for its employees to review.

Amazon's private-label business encompasses more than 45 brands with some 243,000 products, from AmazonBasics batteries to Stone & Beam furniture. Amazon says those brands account for 1% of its $158 billion in annual retail sales, not counting Amazon's devices such as its Echo speakers, Kindle e-readers and Ring doorbell cameras.

Former executives said they were told frequently by management that Amazon brands should make up more than 10% of retail sales by 2022. Managers of different private-label product categories have been told to create $1 billion businesses for their segments, they said.

Amazon has a history of difficult relationships with sellers, especially those that choose not to sell their products on its site. While some of the issues have involved counterfeit goods or frustration about lack of pricing control on their products, another concern for some is that Amazon would use data they accumulate to copy the products and siphon sales.

Because 39% of U.S. online shopping occurs on Amazon, according to research firm eMarketer, many brands feel they can't afford not to sell on the platform. In a recent survey from e-commerce analytics firm Jungle Scout, more than half of over 1,000 Amazon Marketplace sellers said Amazon sells its own products that directly compete with the seller's products. "We had a brand say they wanted to sell exclusively on Walmart, and when we proposed Amazon, they said they don't want to risk private-label copying their product," said Kunal Chopra, the CEO of etailz, which helps vendors sell across platforms.

Early last year, an Amazon private-label employee working on new products accessed a detailed sales report on a car-trunk organizer manufactured by a third-party seller called Fortem, a four-person, Brooklyn-based company run by two 29-year-olds. That employee showed the report to the Journal. More than 33,000 units of the organizer were sold during the 12 months covered in the report, according to a copy reviewed by the Journal. The report has 25 columns of detailed information about Fortem's sales and expenses.

Fortem accounted for 99.95% of the total sales on Amazon for the trunk organizer for the period the documents cover, the data indicate. Oleg Maslakou, one of Fortem's founders, said "no one is selling the Fortem organizer besides us and Amazon Warehouse deals," a resale clearance account of returned or damaged goods from Fortem. "You hit us with a big surprise," he said after reviewing the data Amazon's private-label employee had on his brand.

-

[A Fortem car-trunk organizer sold on Amazon.com, on top, and a competing AmazonBasics version also available on the site. Image source. Click image to open in new window.]

[A car-trunk organizer made by Fortem sits atop a competing product developed by Amazon. Image source. Click image to open in new window.]

Amazon said that there was one other seller of Fortem's trunk organizer during the period of the data the Journal reviewed. It wouldn't comment on how many days that seller was active or how many sales it made. The Journal reached the other seller of the Fortem trunk organizer, who said for the period of time, he only sold 17 units of the item. Fortem's own sales and a slight number of its own damaged goods and returns sold through Amazon's Warehouse Deals account accounted for nearly 100% of the more than 33,000 sales of the unit during the period, the data show.

The data in the report reviewed by the Journal showed the product's average selling price during the preceding 12 months was about $25, that Fortem had sold more than $800,000 worth in the period specified, and that each item generated nearly $4 in profit for Amazon. The report also detailed how much Fortem spent on advertising per unit and the cost to ship each trunk organizer, according to the documents and former Amazon employees who explained their contents.

"We would work backwards in terms of the pricing," said one of the people who used to obtain third-party data. By knowing Amazon's profit-per-unit on the third-party item, they could ensure that prospective manufacturers could deliver a higher margin on an Amazon-branded competitor product before committing to it, said another person who accessed the data.

Fortem launched its trunk organizer on Amazon's Marketplace in March 2016, and it eventually became the No. 1 seller in the category on Amazon. In October 2019, Amazon launched three trunk organizers similar to Fortem's under its AmazonBasics private-label brand. The Fortem trunk organizer detailed in the documents is still a bestseller in the category, Amazon noted. Fortem spends as much as $60,000 a month on Amazon advertisements for its items to come up at the top of searches, said Mr. Maslakou.

Pulling data on competitors, even individual sellers, was "standard operating procedure" when making products such as electronics, suitcases, sporting goods or other lines, said the person who shared the Fortem documentation. Such reports were pulled before Amazon's private label decided to enter a product line, the person said. "Customers' shopping behavior in our store is just one of many inputs to Amazon's private-label strategy," said Amazon. Other factors include fashion and shopping trends and suggestions from manufacturers, it said.

Amazon employees also accessed sales data from Austin-based Upper Echelon Products, according to the data reviewed by the Journal. Its office-chair seat cushion is a popular seller on Amazon. An Amazon private-label employee pulled a year's worth of Upper Echelon data when researching development of an Amazon-branded seat cushion, according to the person who shared the data. An Amazon employee pulled the data early last year. Last September, AmazonBasics launched its own version.

After the Journal disclosed the contents of the sales report to Travis Killian, CEO of seven-person Upper Echelon, he said: "It's not a comfortable feeling knowing that they have people internally specifically looking at us to compete with us." Amazon said there were more than two dozen sellers of the Upper Echelon seat cushion during the period, but declined to specify how many units those sellers sold. Mr. Killian said if that were the case, he isn't sure how the private-label data on his seller account provided to the Journal matched his internal sales data so perfectly.

In traditional retail, a company such as Target Corp. or Kroger Co. places a weekly purchase order with the brands on its shelves. It subsequently owns the inventory, setting the price and discounts. Because of the limitations of shelf space, traditional retailers stock far fewer products than Amazon's hundreds millions of items. Typically, they create private-label products to compete in generic categories such as paper towels, rather than copycat versions of items created by smaller entrepreneurs, private-label executives said. Amazon said the vast majority of its private-label sales are staples such at batteries and baby wipes.

The majority of Amazon's sales -- 58% -- come through third-party sellers, primarily small and medium-size firms that list their items for sale on Amazon's Marketplace platform. (Amazon also buys items directly from manufacturers and sells them directly in "first-party" sales.)

Amazon started making its own products in 2007 with its Kindle e-reader, and it has steadily added new categories and other private-label brand names. Some of its private-label products, such as batteries, have been home runs. Investment firm SunTrust Robinson Humphrey estimates Amazon is on track to post $31 billion in private-label sales by 2022, or nearly double retailer Nordstrom Inc.'s 2019 revenues.

Return to Persagen.com