See also: George Mason University's Historical Hoaxes. Institutionally-Sanctioned Online Disinformation Training.

-

[Image source. Click image to open in new window.]

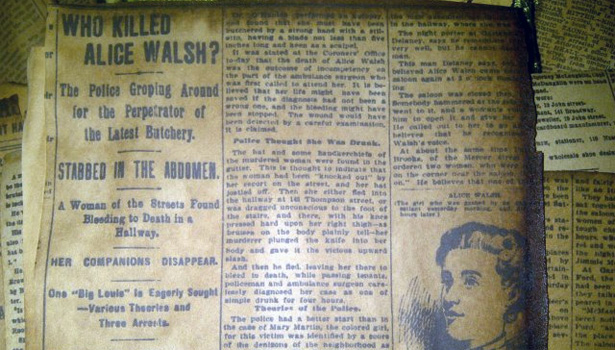

Professor T. Mills Kelly is a historian at George Mason University in Washington, D.C. In 2012, he and students of his course, "Lying About the Past," became headline news after it was uncovered that they had created "false facts" about fictional events and posted them online in blogs, videos and Wikipedia entries.

Professor Kelly believes this method of working-through is true to the learning objectives of the course and, moreover, that it is the best way to instill a deep understanding of practical ethics. Yet he was lambasted for unethical use of the Internet by fellow academics (some of whom had themselves fallen for the hoaxes) and Web developers -- including Wikipedia's Jimmy Wales.

Here, Professor Kelly explains his intentions in devising the original course, how students have become more media literate since that time, and why he believes his university has not approved the course for future syllabi.

What was Lying About the Past?

Lying About the Past was a course I developed designed to teach students greater skepticism about online historical sources (and historical sources in general). The organizing theme of the course was the history of historical hoaxes because I wanted the students to see just how easy (and at the same time how complicated) it was to perpetrate a historical hoax, how easy it was to be fooled by a hoaxer, and at the same time, to have fun while learning about the past.

What was your objective in teaching "Lying About the Past?"

I wanted my students to learn to think critically about the sources they were using in their own research, especially online sources. I wanted them to become just as skeptical about what they were encountering as professional historians are. Teaching students this sort of skepticism is something history educators wrestle with all the time, because students (and the general public) tend to set a pretty low standard when it comes to deciding whether a historical source is one they should trust or not.

At the same time, I wanted my students to have fun. I'm a very popular instructor and so I think it's fair to say that my students enjoy themselves in my classes. But they weren't having fun, by which I mean they weren't laughing, they weren't taking a playful approach to the serious work we were doing, and so on. I don't think fun and serious purpose are antithetical -- just look at the workplace environments created by very successful companies such as Google.

How did it exceed your expectations?

The course, which I've now taught twice, exceeded my expectations in two ways.

First, it really worked when it came to teaching skepticism even as we were having fun. I can't imagine any student who took one or the other iterations of this course ever accepting at first glance any online historical source as being valid. I think they will all continue to be very skeptical about what they are reading or viewing for a very long time.

The other way the course exceeded my expectations -- and this was something I had not anticipated -- was that we spent the entire semester discussing and debating the ethics of the historical profession. After all, what we were doing in the course -- creating historical hoaxes and turning it loose online for two weeks -- skated out onto thin ethical ice. As a result, the ethics of the historical profession were central to our work the entire semester. In the vast majority of history courses, ethics only comes up early in the semester when the professor admonishes his/her students about plagiarism, after which ethics never come up again. That historians spend so little time thinking about the ethics of our profession is evident in the fact that the Library of Congress holds only a few books devoted to the ethics of the professional historian.

Why do you think this method of teaching/structure was so effective?

Central to the teaching of this course was turning my students loose to exercise their creative impulses. Recent research on how young people use digital media indicates that for the rising generation of students, the digital realm is a space of creation (where they make things) as well as a space of extraction (where they go to obtain things). By asking my students to create something, in this case a historical hoax, and then giving them the room to create that thing and put it out into the public domain, I was meeting them where they already live. Because they thought there was just a chance they might fool someone with their hoax, they worked incredibly hard to perfect the hoaxes they were creating. At the same time, because the course challenged them to think critically about ethics, they were doing something they simply don't do in other history courses and the difficulties our work posed forced them to think in ways they generally haven't. And, of course, because they were having fun, they came to class every day excited, engaged, and ready to work hard.

How do you respond to the criticism that the benefit of instilling critical thinking of a very small number of people (your students) doesn't outweigh the cost of "polluting" (as Jimmy Wales described it) the content of the Web for an audience of potential millions?

First of all, I think it's an exaggeration to claim that my students "polluted" the content of the Web. The three hoaxes that they perpetrated were about such obscure topics that had my course not been written about in various media outlets, almost no one would have ever encountered the results of my students' work. So to say that they were somehow polluting the sanctity of the Internet is to claim a much greater importance for their work than is actually warranted.

And that's the way the students wanted it. They wanted their hoaxes to be about obscure, innocuous topics for the very reason that, in our discussions of ethics, they recognized that there were lines they didn't want to cross and one of the important lines was to make sure they were hoaxing about something that just didn't matter.

Second, I think the question plays into a fallacious notion of the Internet as somehow pristine. As we all know, it is riddled with misleading or just downright false content. So, I think that teaching close to 50 students how to be critical consumers of that content, in the ways that I did, was well worth the effort.

The public response is well-known. But less known is how your colleagues and university responded. What was their response? Why?

I think it's fair to say that my course made a number of my colleagues, both here at George Mason and elsewhere, very uncomfortable. And I get that. The course made me uncomfortable. As a historian I've devoted my career to getting things right and so to teach students how to get things intentionally wrong felt wrong to me at many levels, as I'm sure it did to many of my colleagues.

Unfortunately, I was unsuccessful in convincing my colleagues here at Mason that what I was doing in the ways I was doing it had sufficient pedagogical merit that I should be allowed to continue. Instead, our undergraduate committee rejected my proposal to have the course included as a formal course in our catalog (I'd taught it twice under a special topics number). The only way they would have accepted the course was if I agreed that my students would not turn their hoaxes loose online. To my way of thinking, that would reduce the central motivating force of the class -- the need to do excellent work because that work would be public -- into yet another abstract classroom exercise. I was unwilling, for good or ill, to accede to that demand, so I won't be teaching the course any longer.

It's an interesting decision to me for a very specific reason related to the status of teaching versus research in our universities. This is because what my colleagues' decision says is that when it comes to teaching methods, a department can dictate which methods a scholar can or cannot use. I can't imagine that many scholars would tolerate a similar decision about their research methods.

Which elements of Lying About the Past will you incorporate into future syllabi? These can be specific elements, or conceptual content.

The elements of this course that will survive are: playfulness, creativity in the digital space, and a critical examination of historical ethics. I already have the next course sketched out and I will be calling it "Improving the Past."

The past is, as we know, a messy place that could use some cleaning up, if only to make it easier to teach about. My students in this future course will take historical sources and "improve" them in various ways using digital techniques and will then present those improved version online -- not with the intent to hoax anyone, but rather, to generate a conversation about the nature of sources, what it means to do violence to sources (think Stalin's removal of Trotsky from all photographs in the official histories of the revolution in Russia) and what it means to teach about the past through imperfect sources.

Just so no one will be taken in by the improved sources my students create, they will be presented in a way that pairs them with the original so that viewers can easily compare the two.

Which will you discard because of the criticism you received from the wider Web community?

I won't be making any changes because of criticism I received from the wider Web community. While I was very interested in the conversation that erupted across the Internet last May [2012] about my course, there was nothing in that discussion that caused me to reconsider anything that I or my students had done.

You taught the course twice, four years apart. The "hoax" was discovered far more quickly the second time around. Does this suggest people are becoming more critical of online content, or did your students simply tread into an expert community, which was naturally more dogmatic than the general Web browser?

It's worth remembering that only one of the two hoaxes my students created was called out by the community they tried to hoax (serial killer enthusiasts on Reddit). The other hoax lasted the full two weeks and was then simply exposed by its creators. A dataset of three hoaxes isn't really enough evidence to draw any definitive conclusions, so I'll simply speculate that what happened with the serial killer hoax was, as you suggest, a case of the students choosing an expert community that was better able to ferret out that their work was a hoax.

Return to Persagen.com