Book Bans Are Targeting the History of Oppression

| URL |

https://Persagen.com/docs/book_bans_are_targeting_the_history_of_oppression.html |

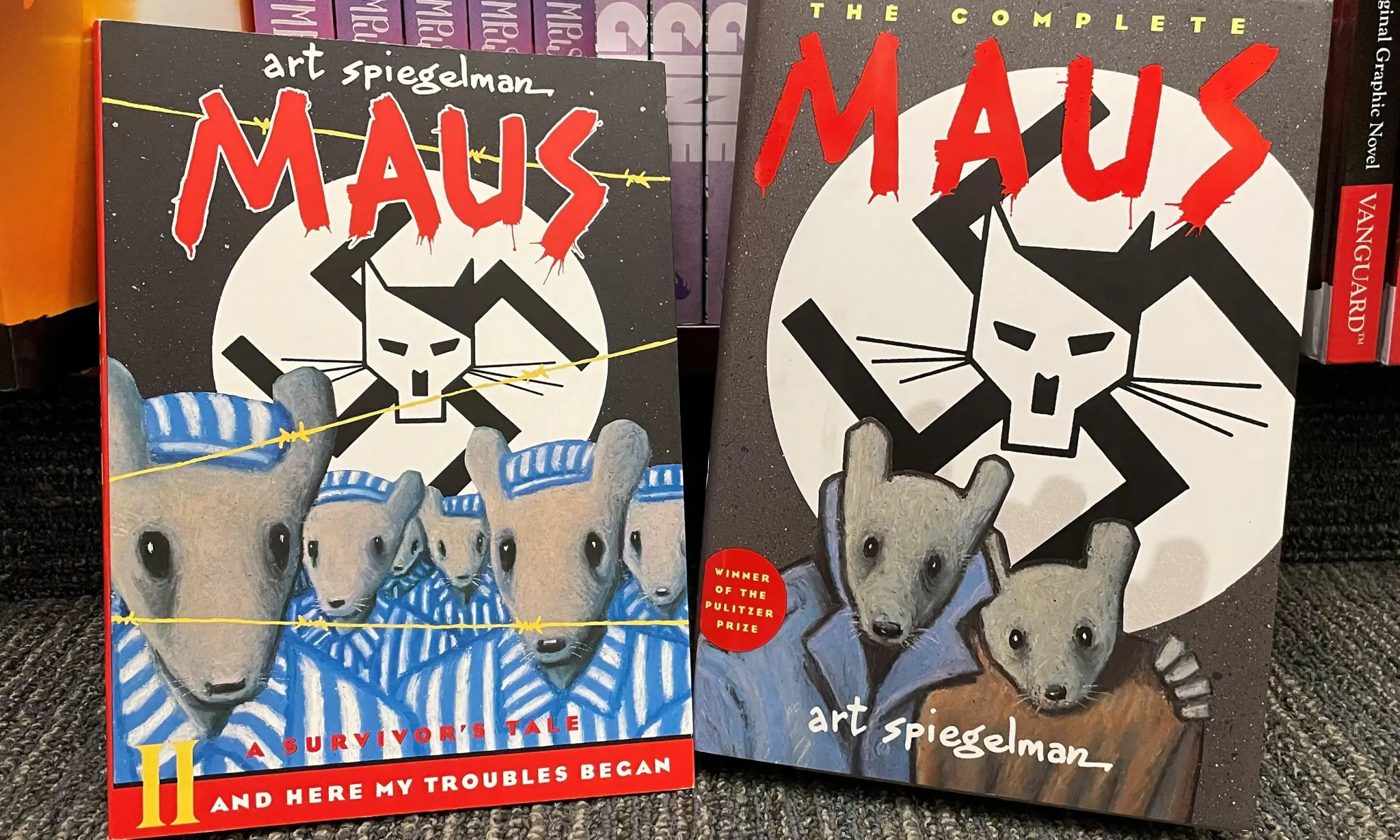

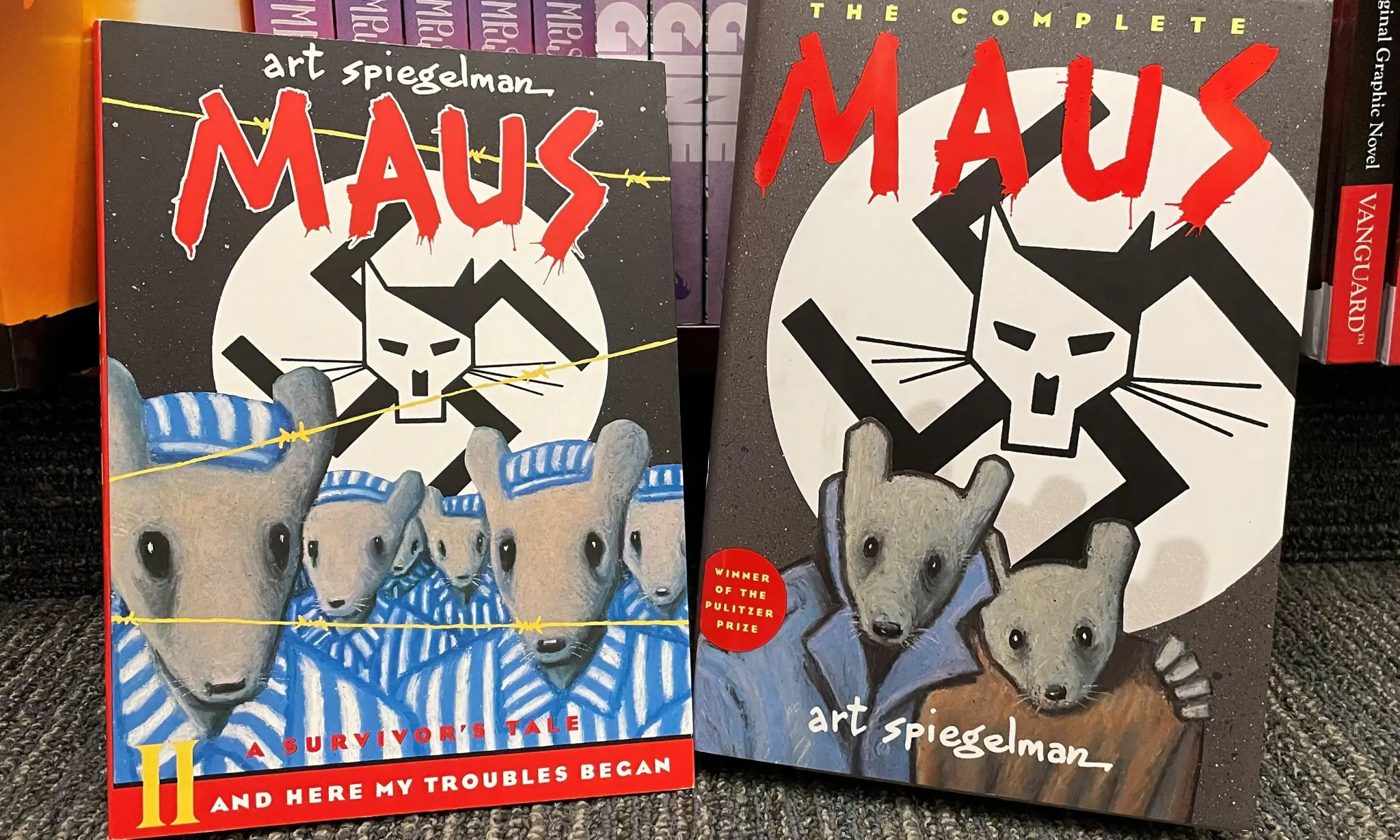

Maus (Art Spiegelman)

Holocaust book Maus hits bestseller list after

Tennessee school board ban. [image source]

|

| Sources |

Persagen.com | other sources (cited in situ) |

| Source URL |

https://www.theatlantic.com/family/archive/2022/02/maus-book-ban-tennessee-art-spiegelman/621453/ |

| Title |

Book Bans Are Targeting the History of Oppression |

| Subtitle |

The possibility of a more just future is at stake when young people are denied access to knowledge of the past |

| Author |

Marilisa Jiménez García [biography: Marilisa Jimenez Garcia | local copy] is an associate professor of Latinx studies and English and the founding director of the Institute on Critical Race and Ethnic Studies at Lehigh University (Bethlehem, Pennsylvania). She is the author of Side by Side: U.S. Empire, Puerto Rico, and the Roots of American Youth Literature and Culture. |

| Date published |

2022-02-02 |

| Curation date |

2022-02-02 |

| Curator |

Dr. Victoria A. Stuart, Ph.D. |

| Modified |

|

| Editorial practice |

Refer here | Date format: yyyy-mm-dd |

| Summary |

The possibility of a more just future is at stake when book bans deny young people access to knowledge of the past. "Maus" and many other banned books that grapple with the history of oppression show readers how personal prejudice can become the law. |

| Main article |

Censorship |

| Key points |

|

| Related |

|

|

Show

"Maus" is likely a literary reference to the infamous Nazi board game Juden Raus! (1936; Jews Out!) -- which became a slogan shouted out during Kristallnacht, a pogrom against Jews carried out by the Nazi Party's Sturmabteilung (SA) paramilitary forces along with civilians throughout Nazi Germany on 1938-11-{09-10}. The streets were full of people shouting: "Juden Raus! ..."

|

| Keywords |

Show

- anti-racist | critical race theory | death | democracy | ethnic profiling | graphic novel | graphic-narrative | graphic-novel | history of oppression | imperialism | imprisonment | nonfiction | oppression | postmodernist | racial profiling | racism | suicide

|

| Keyphrases |

Show

- American cartoonist

- Anne Frank's "The Diary of a Young Girl" has been flagged as inappropriate

- avant-garde comics and graphics magazine

- banned books that grapple with the history of oppression

- best-selling and award-winning books

- book bans deny young people access to knowledge of the past

- books' educational and artistic value

- censoring young people's ability to learn about historical and ongoing injustices

- controversial issues

- Critics have classified "Maus" as memoir, biography, history, fiction, autobiography, or a mix of genres

- despite arguing for protecting children from controversial subjects, Tennessee has incarcerated children as young as 7 and disrupting the lives of undocumented youth

- displays innovation in its pacing, structure, and page layouts

- districts across the United States have banned

- districts across the United States have banned anti-racist instructional materials as well as books that tackle themes of racism and imperialism

- effects of racism on a young Black girl's self-image

- goal being to "never forget"

- harsh language or gruesome imagery

- instinct to ban books in schools

- instructional materials

- latest in a series of school book bans

- mainstream attention

- Maus depicts Art Spiegelman interviewing his father about his experiences as a Polish Jew and Holocaust survivor

- minimalist drawing style

- no one foresaw a day when there could be a valid opposing view of The Holocaust

- Nobel Prize-winning author

- Pennsylvania book ban was later reversed

- Pennsylvania school board

- personal prejudice can become the law

- possibility of a more just future is at stake

- recognize that language and imagery may be integral to showing the harsh, gruesome truths of the books' subjects

- recorded interviews became the basis for the graphic novel

- removed from shelves in school districts in Missouri and Florida

- represents Jews as mice, Germans as cats

- sanitization of history

- seek to keep young people from reading about history's horrors

- targeting books that teach the history of oppression

- teach students about diversity

- teaching of Holocaust literature and survivor testimonies

- Tennessee school board recently pulled

- Texas instructed teachers to present opposing views about The Holocaust

- Texas legislators

- Texas school-district administrator invoked a law that requires teachers to present opposing viewpoints

- young Jewish girl hiding from the Nazis to avoid being taken to a concentration camp

|

| Named entities |

Show

- Anne Frank | Annelies Marie (Anne) Frank | Art Spiegelman | Auschwitz | Auschwitz concentration camp | Beloved | Chloe Anthony Wofford Morrison | Chloe Ardelia Wofford | Françoise Mouly | historical negationism | historical revisionism | Holocaust | Ijeoma Oluo | Itzhak Avraham ben Zeev Spiegelman | Lois Lowry | Maus | Nazi concentration camps | New York City | Newbery Medal | Number the Stars | Polish Jew | Pulitzer Prize | Raw (magazine) | So You Want to Talk About Race | Special Award in Letters | Spiegelman | Tennessee | The Bluest Eye | The Diary of a Young Girl | The Holocaust | The York Dispatch | Toni Morrison | U.S. | United States | Vladek Spiegelman | World War II | York County, Pennsylvania

|

| Ontologies |

Show

- Culture - Cancel Culture

- Culture - Cultural studies - Media culture - Deception - Media manipulation - Propaganda - Propaganda techniques - Historical negationism

- Culture - Cultural studies - Media culture - Deception - Media manipulation - Propaganda - Propaganda techniques - Historical revisionism

- Science - Formal sciences - Information science - Intellectual freedom

- Science - Social sciences - Psychology - Behaviorism - Conformity - Enforcement - Proscription - Censorship

- Science - Social Sciences - Psychology - Behaviorism - Conformity - Enforcement - Proscription - Censorship - Cancel culture

- Google LLC - Issues - Censorship

- Society - Critical theory - Critical race theory

- Society - Issues - Censorship

- Society - Issues - Education - Christian right

- Society - Issues - Free Speech

- Society - Issues - Discrimination - Anti-LGBT discrimination - Homophobia

- Society - Issues - Discrimination - Anti-LGBT discrimination - Transphobia

- Science - Issues - Integrity - Fraudulent science - Pseudoscience - Pseudohistory

- Society - Issues - Religion - Christian right

- Society - Politics - Political ideologies - Conservatism

- Society - Politics - Political ideologies - Conservatism - Social conservatism - Religious conservatism - Christian right

- Technology - Internet - Internet censorship

- Technology - Internet - Social media - Censorship

- Science - Social Sciences - Psychology - Behaviorism - Conformity - Enforcement - Proscription - Censorship - Cancel culture

|

Background: Maus

Source: Wikipedia, 2022-02-02.

Maus is a nonfiction graphic-narrative book by American cartoonist Art Spiegelman. Serialized from 1980 to 1991, Maus depicts Spiegelman interviewing his father about his experiences as a Polish Jew and Holocaust survivor. Maus employs postmodernist techniques and represents Jews as mice, Germans as cats, Poles as pigs, Americans as dogs, the English as fish, the French as frogs, and the Swedish as deer. Critics have classified Maus as memoir, biography, history, fiction, autobiography, or a mix of genres. In 1992, Maus became the first (and to date only) graphic novel to win a Pulitzer Prize (the Special Award in Letters).

In the frame-tale timeline, the narrative present begins in 1978 in New York City, where Art Spiegelman talks with his father Vladek Spiegelman about his Holocaust experiences, gathering material and information for the Maus project he is preparing. In the narrative past, Spiegelman depicts these experiences, from the years leading up to World War II to his parents' liberation from the Nazi concentration camps. Much of the story revolves around Spiegelman's troubled relationship with his father, and the absence of his mother, who died by suicide when he was 20. Her grief-stricken husband destroyed her written accounts of Auschwitz. The book uses a minimalist drawing style and displays innovation in its pacing, structure, and page layouts.

A three-page strip also called "Maus" that Art Spiegelman made in 1972 gave Spiegelman an opportunity to interview his father about his life during World War II. The recorded interviews became the basis for the graphic novel, which Spiegelman began in 1978. Art Spiegelman serialized Maus from 1980 until 1991 as an insert in Raw (magazine), an avant-garde comics and graphics magazine published by Spiegelman and his wife, Françoise Mouly, who also appears in Maus. A collected volume of the first six chapters that appeared in 1986 brought the book mainstream attention; a second volume collected the remaining chapters in 1991. Maus was one of the first graphic novels to receive significant academic attention in the English-speaking world.

Main Article: Book Bans Are Targeting the History of Oppression

Source: [theAtlantic.com, 2022-02-02] Book Bans Are Targeting the History of Oppression. The possibility of a more just future is at stake when young people are denied access to knowledge of the past.

The instinct to ban books in schools seems to come from a desire to protect children from things that the adults doing the banning find upsetting or offensive. These adults often seem unable to see beyond harsh language or gruesome imagery to the books' educational and artistic value, or to recognize that language and imagery may be integral to showing the harsh, gruesome truths of the books' subjects. That appears to be what's happening with Art Spiegelman's Maus - a Pulitzer Prize-winning graphic-novel series about the author's father's experience of The Holocaust that a Tennessee school board recently pulled from an eighth-grade language-arts curriculum, citing the books' inappropriate language and nudity.

The Maus case is one of the latest in a series of school book bans targeting books that teach the history of oppression. So far during this school year alone 2021-2011], districts across the United States have banned many anti-racist instructional materials as well as best-selling and award-winning books that tackle themes of racism and imperialism. [See also: critical race theory.] For example, Ijeoma Oluo's So You Want to Talk About Race was pulled by a Pennsylvania school board, along with other resources intended to teach students about diversity, for being "too divisive," according to the The York Dispatch (a morning newspaper serving the people of York County, Pennsylvania). [Update: that Pennsylvania book ban was later reversed.] Nobel Prize-winning author Toni Morrison's book The Bluest Eye - about the effects of racism on a young Black girl's self-image - has recently been removed from shelves in school districts in Missouri and Florida (the latter of which also banned Toni Morrison's book Beloved). What these bans are doing is censoring young people's ability to learn about historical and ongoing injustices.

For decades, U.S. classrooms and education policy have incorporated the teaching of Holocaust literature and survivor testimonies, the goal being to "never forget". Maus is not the only book about The Holocaust to get caught up in recent debates on curriculum materials. In 2021-10 a Texas school-district administrator invoked a law that requires teachers to present opposing viewpoints to "widely debated and currently controversial issues," instructing teachers to present opposing views about The Holocaust in their classrooms. Books such as Lois Lowry's Number the Stars - a Newbery Medal winner about a young Jewish girl hiding from the Nazis to avoid being taken to a concentration camp - and Anne Frank's The Diary of a Young Girl have been flagged as inappropriate in the past, for language and sexual content. But perhaps no one foresaw a day when it would be suggested that there could be a valid opposing view of The Holocaust.

In the Tennessee debate over Maus, one school-board member was quoted as saying: "It shows people hanging, it shows them killing kids, why does the educational system promote this kind of stuff? It is not wise or healthy." This is a familiar argument from those who seek to keep young people from reading about history's horrors. But children, especially children of color and those who are members of ethnic minorities, were not sheltered or spared from these horrors when they happened. What's more, the sanitization of history [historical revisionism | historical negationism] in the name of shielding children assumes, incorrectly, that today's students are untouched by oppression, imprisonment, death, or racial profiling and ethnic profiling. (For example, Tennessee has been a site of controversy in recent years for incarcerating children as young as 7 and disrupting the lives of undocumented youth.

The possibility of a more just future is at stake when book bans deny young people access to knowledge of the past. For example, Texas legislators recently argued that coursework and even extracurriculars must remain separate from "political activism" or "public policy advocacy." They seem to think the purpose of public education is so-called neutrality - rather than cultivating informed participants in democracy.

Maus and many other banned books that grapple with the history of oppression show readers how personal prejudice can become the law. The irony is that in banning books that make them uncomfortable, adults are wielding their own prejudices as a weapon, and students will suffer for it.

Additional Reading

[theConversation.com, 2022-02-08] Banning "Maus" only exposes the significance of this searing graphic novel about The Holocaust.

[Thomson Reuters Foundation: news.Trust.org, 2022-02-04] U.S. school books - the latest LGBTQ+ rights battleground. Bills proposed in almost a dozen U.S. states seek to crack down on books and lessons with LGBTQ+ themes.

[DemocracyNow.org, 2022-02-02] The Silencing of Black & Queer Voices: George M. Johnson on 15-State Ban of "All Boys Aren't Blue".

[MotherJones.com, 2022-02-01] The Inside Story of the Banning of "Maus." It's Dumber Than You Think. I read the minutes of the McMinn County, Tennessee, school board so you don't have to.

Return to Persagen.com